Anthea Bell as photographed by Gil Roth, who interviewed her in 2015.

I was enormously saddened to hear of the death of the great Anthea Bell, whom I’d admired from afar for many years but unfortunately never got the chance to meet. The revered translator of W.G. Sebald and the Asterix comics, but also Kafka (The Castle), Hans Christian Andersen, Stefan Zweig, Siegfried Lenz, Karen Duve, Hans Magnus Enzensberger, Saša Stanišić, Eugen Ruge, and many others, she was also the queen of children’s literature in translation, and her work repeatedly (seven times!) won her publishers the Mildred L. Batchelder Award, for books by René Goscinny, Bjarne Reuter, and Christine Nöstlinger. Her translations were also recognized with the Independent Foreign Fiction Prize, the Schlegel-Tieck Prize (4 times!), the Oxford-Weidenfeld Translation Prize, and the Marsh Award for Children’s Literature in Translation. In 2010 she was appointed Officer of the Order of the British Empire, and in 2015 awarded the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany.

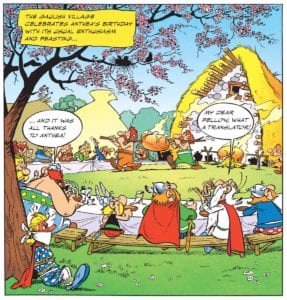

Above all, she was known for her artistry and inventiveness that was nowhere more visible than in her playful Asterix translations that won the hearts of generations of young readers.  She hilariously named Obelix’s dog Idéfix (idée fixe) Dogmatix, for example. On the occasion of her death, her son Oliver Kamm tweeted an Asterix birthday greeting. Of course it makes sense that these adventurous Gauls loved her as much as she loved them. I wish I could have met her too before it was too late.

She hilariously named Obelix’s dog Idéfix (idée fixe) Dogmatix, for example. On the occasion of her death, her son Oliver Kamm tweeted an Asterix birthday greeting. Of course it makes sense that these adventurous Gauls loved her as much as she loved them. I wish I could have met her too before it was too late.

Since I didn’t know her and thus can’t write a personal tribute, I asked her friend and colleague Shelley Frisch – herself a respected and much-lauded translator – to write a few words of remembrance. This is what she wrote:

To know Anthea Bell is to love her. Those who never met her in person—as well as those who did—treasure her inspired translations, from A(sterix) to Z(weig). Her devoted followers include readers of all ages who have delighted in her clever word play (“PUNditry,” especially in Asterix) and her manifest joy in language’s myriad mutations. And they are grateful to have new dimensions of world literature brought to their (English-language) door in such splendid fashion.

I first met Anthea more than a decade ago during one of her trips to the US, when we were drawn together by a single word (Wandlerin) in a Cornelia Funke book she was translating from the German. The word intrigued us both. I can’t recall what rendering we eventually settled on, but “shape-shifter” was definitely a finalist. After much amusing rumination on this word, Anthea and I settled into a lively and regular transatlantic correspondence about, as they say in German, “Gott und die Welt” (everything under the sun, that is), and this correspondence continued on for several delightful years. Each cheered on the other’s awards and publications, and there was a good deal of shoptalk, especially, but by no means exclusively, about “our” Kafka. We bemoaned marketing departments’ notions of what makes a book attractive to buyers. (For Anthea’s translation of Julia Franck’s Die Mittagsfrau, the unpalatable solution of The Lunch Ladywas proposed, while she advocated for The NoondayWitch, or Lady Midday; the eventual compromise was The Blind Side of the Heart. I knew this feeling well; I’d recently had to agree to the subtitle “The Decisive Years” for one of the Kafka biography volumes, although Kafka was the least decisive person ever to walk the planet.)

Beyond these exchanges, though, was what I treasured most about our correspondence: nuggets of wisdom on a wide range of literary subjects combined with witty repartee about the “stuff” of daily life. We commiserated over back and hip pains, and giggled together about having to resort periodically to what we termed the “geriatric shuffle” (a normally ungiggly phenomenon; indeed, I’m doing that very dance these days), and concurred that going up a flight of stairs was far easier than going down, no matter what others might think. We groaned at her doctors’ insistence that “a stiff upper lip” was the best and only cure, and blasted her recent stay in the hospital for sending her home with a leg ulcer she had acquired there.

We delighted in the fact that we both had journalist sons. (Her younger son, Oliver Kamm, had left the world of investment banking “just as it was turning into a sphere of ill repute.”) Later on, in the sheerest of coincidences, Oliver praised Reiner Stach’s Kafka biography (in my translation) in the pages of the Times (London), upon which Anthea wrote me, to clarify, “I don’t think Oliver has the faintest idea that I know you!”

I could go on and on: there are delightful passages in her letters about the origins of her last name (nothing bell-like about it) and that of her ex-husband, Antony Kamm. (“Kamm, although a short and simple name, is difficult for the British to spell (you get Kahn, Cohen, Khan, Kamen, all sorts of permutations). I guess that Antony’s forebears lived on the crest of hills or mountains somewhere in Germany, and that is the sort of Kamm involved, nothing involving the use of a comb.”)

I’ll add one last Kafka comment here, though there’s so much more I could say. In 2010, Anthea wrote me this: “Only when I was translating The Castle did I see its affinity with Alice Through the Looking Glass. At times the landlady of the Bridge Inn, Gardena, could be a dead ringer for the Red Queen.” I continue to ponder this captivating comparison between two of my favorite books.

I sorely miss Anthea Bell already. She was a friend and colleague of rare wit and talent, and, most importantly, of generosity and kindness. We are lucky to have had her in our world, and fortunate that even in her absence, we can revel in the brilliant writing she left for current and future generations to enjoy.

Shelley Frisch