It’s the practice of New York Review Books Classics to ask each of their authors and translators to write a letter about a forthcoming book for distribution to the NYRB mailing list and publication on their website. Here’s what I wrote about Berlin Stories by Robert Walser:

In 1905 Robert Walser packed his bags and left behind his native Switzerland for the bustling metropolis of Berlin. The fledgling author, twenty-seven years of age, had just published his first book of fiction, Fritz Kochers Aufsätze (Fritz Kocher’s Essays), and moving to Berlin was the obvious next step for him to take in the pursuit of a proper literary career. Just a year before he had  been supporting himself as an on-again-off-again bank clerk and copyist, but now he was looking to become a proper novelist, an endeavor that would require all his strength. When he arrived in the German capital, he moved into the apartment of his brother Karl, a painter, who had made the pilgrimage to Berlin the year before and quickly established himself as the foremost stage set designer of the age.

been supporting himself as an on-again-off-again bank clerk and copyist, but now he was looking to become a proper novelist, an endeavor that would require all his strength. When he arrived in the German capital, he moved into the apartment of his brother Karl, a painter, who had made the pilgrimage to Berlin the year before and quickly established himself as the foremost stage set designer of the age.

Walser soon discovered, however, that his brother’s high-society lifestyle was not to his liking. The fancy soirées they attended made him feel like a bumpkin, and he soon developed a reputation for uncouth conduct. Karl would receive invitations to dinner specifying he could bring Robert “only if he wasn’t too hungry.” It may well have been this gentrified arts scene in which artists and their patrons socialized together that made Walser decide to enroll, only a few months after his arrival, in Berlin’s Aristocratic Servants School. Here he studied the art of waiting on table, polishing shoes, and shaking out carpets. When he graduated, he took a job as an assistant butler at a count’s castle in Silesia, where he spent the better part of the winter. His publisher was instructed to send him letters only in unmarked envelopes, since he didn’t want his employers to know he was a writer.

He was a writer, though, and remained true to his craft. Over the next three years he would write and publish three novels: The Tanners, The Assistant, and Jakob von Gunten, as well as producing scores of short pieces for publication in magazines and newspapers. Berlin Stories collects all the short work Walser wrote in Berlin about Berlin, as well as a selection of later pieces in which he looks back on his life in the metropolis. These stories are the record of a city in the throes of modernity. Berlin was already a vast metropolis, one of the great cities of Europe. It got its first subway in 1902; thirty-five different streetcar lines converged at Potsdamer Platz; and automobiles zipped in and out among hackney carriages on its crowded streets.

If the city was on the move, so was Walser. He walked the streets collecting impressions. He was a fast writer, and liked to write about things in rapid motion. In “Aschinger” he describes a Berlin-style fast-food restaurant, and his walk stories—like “Good morning, Giantess!”—show us the city as a blur of glimpses. “In the Electric Tram” talks about learning how to sit when riding in this newfangled vehicle, and “Full” features a monologue by a disgruntled omnibus conductor.

“A metropolis,” Walser writes, “is a giant spiderweb of squares, streets, bridges, buildings, gardens, and wide, long avenues […], a wave-filled ocean that for the most part is still largely unknown to its own inhabitants, an impenetrable forest, an opulent, overgrown, huge, forgotten, or half-forgotten park, a thing that has been built up too extensively for it to ever again be oriented within itself.” A fire breaking out in the city produces a “thick, seemingly incessant rain of small, light sparks and embers [that] flies out of the dark air and down into the crowded street, sowing a crop of glowing snow.” The wonder that the city and its life inspired in him is evident in the vibrancy of his sentences, and I have taken pains to let the vividness of his impressions enliven the prose of my translation as well.

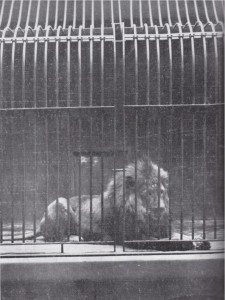

Finally, Berlin was also a city of the theater for Walser, something he experienced both as an audience member and through his brother’s work and friends. The young author had started out dreaming of becoming an actor, even auditioning once for the celebrated Josef  Kainz (who pronounced the teenage enthusiast devoid of thespian talent). Throughout his life Walser maintained his love of the stage and wrote a great deal about performances in Berlin, including both high art (“On the Russian Ballet”) and low (“Cowshed”). My favorite of his theater texts here is the one entitled “An Actor,” devoted to a lion in Berlin’s Zoological Garden; this actor is a cousin to Rilke’s famous panther.

Kainz (who pronounced the teenage enthusiast devoid of thespian talent). Throughout his life Walser maintained his love of the stage and wrote a great deal about performances in Berlin, including both high art (“On the Russian Ballet”) and low (“Cowshed”). My favorite of his theater texts here is the one entitled “An Actor,” devoted to a lion in Berlin’s Zoological Garden; this actor is a cousin to Rilke’s famous panther.

Walser left Berlin in 1912, never to come back. His Berlin Stories offer a wonderful kaleidoscopic portrait of this city that both entranced and overwhelmed him, a mixed response that made its way into these stories—at times he describes the advent of modernism’s technologies as almost hostile. For him, city life is best perceived not from the back seat of an automobile but by walking the streets, whether first thing in the morning or late at night. These stories are records of a quite particular time and place, but also of a very unusual sensibility, one whose quizzical shaping gaze presents the city as a terra incognita of intoxicating possibility.