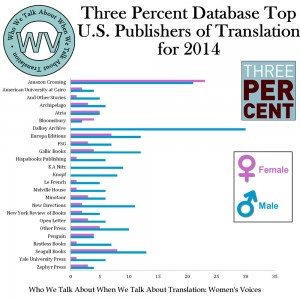

Yesterday I sat on a panel entitled “Who We Talk About When We Talk About Translation: Women’s Voices” at the PEN World Voices Festival. The panel, sponsored by the PEN Translation Committee, was the brainchild of Co-Chair Margaret Carson, who had impressively crunched a lot of numbers borrowed from Three Percent’s amazing Translation Database that were transformed by VIDA graphmeister David Fitzgerald into a series of revealing tables showing gender distribution in the translated works published by a number of U.S. presses as well as those selected for translation prizes. The results came as a surprise to me: I hadn’t expected to see quite so enormous a disparity, including among some publishers dear to my heart. But that’s the usefulness of numbers: They force us to think concretely about issues we might otherwise have brushed aside. Here’s the graph showing the proportions between male and female writers in translation brought out in 2014 by the top two dozen U.S. houses for works in translation.  (N.B. we’re talking about the gender of the original author here, not that of the translator.) The worst offender was Dalkey Archive, which published 30 books last year, every last one of them by a male author. On the other end of the spectrum is Amazon Crossing, which published both the most translated books overall and the most translated books by women. I’m going to hazard a guess that the explanation for their woman-friendly stats is that they publish mostly genre fiction, an area in which women are published much more widely in many languages than in literary fiction. Which, yes, is problematic. (As is, by all accounts, the way Amazon has been going about finding translators for these genre fiction books [via an online bidding system] and contracting for their work [pay rumored to be very low, but details unavailable thanks to Amazon’s love of the non-disclosure agreement]).

(N.B. we’re talking about the gender of the original author here, not that of the translator.) The worst offender was Dalkey Archive, which published 30 books last year, every last one of them by a male author. On the other end of the spectrum is Amazon Crossing, which published both the most translated books overall and the most translated books by women. I’m going to hazard a guess that the explanation for their woman-friendly stats is that they publish mostly genre fiction, an area in which women are published much more widely in many languages than in literary fiction. Which, yes, is problematic. (As is, by all accounts, the way Amazon has been going about finding translators for these genre fiction books [via an online bidding system] and contracting for their work [pay rumored to be very low, but details unavailable thanks to Amazon’s love of the non-disclosure agreement]).

These issues have been in the air for several years, thanks to the pioneering work of VIDA (which you absolutely should investigate ASAP if you don’t already know it). Yesterday’s panelists included VIDA’s great number-cruncher, Jen Fitzgerald, in charge of producing the VIDA Count figures for the first five years of VIDA’s existence (i.e. until this year). Rob Spillman, who received one of the inaugural VIDO awards from VIDA for his work as the editor of Tin House, was on the panel as well, along with novelist Véronique Tadjo (currently of Witwatersrand, though she has roots in France and the Côte d’Ivoire). Margaret Carson co-moderated along with Alta Price and gave us quite the slide show.

Listening to Fitzgerald and Spillman talk about VIDA’s work and its effects was inspiring. Some publishers have responded defensively to the VIDA Count (e.g. see TLS editor Peter Stothard saying he’s pleased to be moving towards a “closer balance” in his journal even though less than one third of his reviewers last year were women). Spillman’s response when the first VIDA count was published in 2010 was to start reviewing Tin House’s internal statistics, and what he found was that while the TH staff thought they were publishing roughly equal numbers of men and women, they weren’t. But a year later TH was achieving parity (and has ever since), largely through revised strategies for soliciting work. Spillman says that while he had always solicited work from equal numbers of men and women, the men were twice as likely to respond by sending him work. And women who were rejected with a generic note inviting them to resubmit were one quarter as likely to do so as their male peers. Being rejected seemed to have a different effect on the women. So Spillman began putting more effort into making his rejection notes more explicitly encouraging and following up with requests for additional submissions. By pursuing authors more persistently, he soon found more work by female authors that he wanted to print.

And what about the translation world? When it comes to the authors having their work translated and winning translation prizes in the U.S., Carson’s figures show a strong gender bias overall. And while male and female translators are getting their translations published in similar numbers, the major U.S. translation prizes (National Translation Award, PEN Translation Prize, PEN Award for Poetry in Translation, Best Translated Book Award) have been going overwhelmingly to male translators. I wonder whether the female translators winning the major awards are more likely to win them for translations of male authors; this would require even more number-crunching to determine.

In any case, it appears that female authors are likely to have female translators. Véronique Tadjo weighed in on this question, noting that every time a work of hers has been translated into English (9 books to date, including 4 YA titles), it’s been because a translator has championed her work – and all of these have been women. This was apparently the case even for The Shadow of Imana, Travels in the Heart of Rwanda (Oxford: Heinemann, 2002) – an important work researched in Rwanda after the genocide. Tadjo pointed out how difficult it is for a francophone writer to get noticed internationally – her language and nationality puts her in the minority both among African writers and among writers of French. It’s also a significant problem in Africa that there is so little translation happening between the many African languages – the reliance on colonial languages for communication among peoples is obviously problematic. Many writers turn to French or English for their literary work in the hope of reaching a wider audience – and does this mean they are catering to a Western readership? Most of the authors she knows who still write indigenous languages are women.

In my own contribution to the panel, I spoke about the need for a prize to recognize translated work by women. This is something I’ve been talking about on this blog for months now, following the lead of Katy Derbyshire, who’s been writing about this for the past year (and just spoke on the issue at the London Book Fair). Katy’s prize in the U.K. is still in the works, and I think we should get one in the works in the U.S. too. So what sort of prize should it be, and should it be independent or administered by another entity? If it’s a prize for a translated book by a woman (a prize for the author with no thought to the translator), we translators might approach VIDA and ask if they would consider adding a prize for a translated work by a woman to their array of prizes (new this year!). If it’s a prize for both the book and the translator, it might be administered by ALTA. Or it might be independent, administered by a to-be-formed coalition of women and allies. At some point, too, the definitions of such a prize should take the inadequacies of the gender binary into consideration as well

Rob Spillman suggested that Tin House might create an award for a translation-in-progress of a work by a female author – the prize would consist of publication by Tin House Press with a proper contract and advance. I think that’s a splendid idea and offered my help getting such a competition off the ground. Michael Reynolds of Europa Editions suggested from the audience the creation of an acquisition grant for publishers to encourage them to print books by women. I think that would be terrific too, but if I’m going to fundraise for something, I want the $ to go directly into the hands of translators. Europa already comes in around the middle of the pack in terms of gender parity, with 37% translated female authors last year, assuming the person writing under the pseudonym “Elena Ferrante” is definitely a woman. (Does anyone know? Rebecca Falkoff has an interesting theory.)

Meanwhile literature in translation would appear to be flourishing in this country – Katrine Jensen, who’s serving as a Best Translated Book Award juror, reported that there were 500 submissions in the Fiction category this year. That’s a nice juicy batch of translations.

Oh, and a pro tip from Jen Fitzgerald: posting on social media is a great way to bring attention to issues like this, and she encourages the use of hashtags like #TranslateWomen or @Biblibio‘s #womenintranslation in posts relating to the topic. Sounds good to me.

I attended two other splendid translation events at PEN World Voices this week as well (the Translation Slam and the panel on blogging about translated literature), but this post is already too long, so I’ll have to report on them later. Meanwhile, keep an eye on Words without Borders, which sent bloggers to all the translation-related PWV events this year (with reports still coming in as of this writing).