I was heartbroken to learn this evening of the death of Gregory Rabassa (1922 – 2016), the beloved elder statesman of the New York translation community whose impish presence and endlessly flowing wisecracks belied the decades of steadfast labor by means of which he filled all our bookshelves with dozens of great works by Spanish-language authors that became key inspirational texts in the English-language literary canon. He was 94 years old. Beginning with his very first translation, Julio Cortázar’s novel Hopscotch in 1966, and his second, Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude in 1970, he staked out literary turf as a translator that soon became internationally renowned as the Latin American “Boom” – some of the greats he translated included Jorge Luis Borges, Mario Vargas Llosa, Machado de Assis, Clarice Lispector, José Lezama Lima,

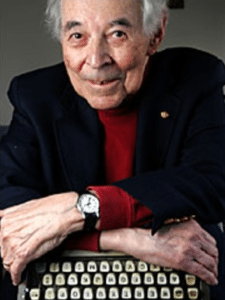

I was heartbroken to learn this evening of the death of Gregory Rabassa (1922 – 2016), the beloved elder statesman of the New York translation community whose impish presence and endlessly flowing wisecracks belied the decades of steadfast labor by means of which he filled all our bookshelves with dozens of great works by Spanish-language authors that became key inspirational texts in the English-language literary canon. He was 94 years old. Beginning with his very first translation, Julio Cortázar’s novel Hopscotch in 1966, and his second, Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude in 1970, he staked out literary turf as a translator that soon became internationally renowned as the Latin American “Boom” – some of the greats he translated included Jorge Luis Borges, Mario Vargas Llosa, Machado de Assis, Clarice Lispector, José Lezama Lima,  António Lobo Antunes, Miguel Ángel Asturias, Jorge Amado, and more. Rabassa taught for years in the City University of New York system, both at Queens College and the Graduate Center, where some incredibly lucky students got to take his translation classes. When I interviewed him three years ago for The Rumpus, he told me how he liked to assign his students playful exercises such as making them chain-translate texts via several successive languages so as to be able to analyze in the end what words remained intact after this telephone game and why. It must have been so much fun as well as instructive to take his classes. I’m just glad I was fortunate enough to hear him speak several times, to intersect with him at conferences (you could always tell where he was – it was always in the middle of a little group of people convulsed with laughter), and to interview him. I know that a great deal will be written about him over the next days and weeks, and I look forward to

António Lobo Antunes, Miguel Ángel Asturias, Jorge Amado, and more. Rabassa taught for years in the City University of New York system, both at Queens College and the Graduate Center, where some incredibly lucky students got to take his translation classes. When I interviewed him three years ago for The Rumpus, he told me how he liked to assign his students playful exercises such as making them chain-translate texts via several successive languages so as to be able to analyze in the end what words remained intact after this telephone game and why. It must have been so much fun as well as instructive to take his classes. I’m just glad I was fortunate enough to hear him speak several times, to intersect with him at conferences (you could always tell where he was – it was always in the middle of a little group of people convulsed with laughter), and to interview him. I know that a great deal will be written about him over the next days and weeks, and I look forward to  reading all these remembrances. Meanwhile a great way to learn about his fascinating life is to read his 2005 memoir If This Be Treason: Translation and Its Dyscontents, and you won’t want to miss the part about him serving as a cryptographer in WWII – surely outstanding preparation for a future translator – nor his really interesting thoughts about, for example, how the sounds of a language can influence the style of translations from that language. “He’s the godfather of us all,” Edith Grossman (herself one of the most revered translators alive) told the Associated Press earlier today. If there’s a translators’ heaven, you can be sure that Constance Garnett, Ralph Manheim, Michael Henry Heim, and William Weaver have saved a seat at the banquet table for him. I’m sure they’ll have a lot to talk about.

reading all these remembrances. Meanwhile a great way to learn about his fascinating life is to read his 2005 memoir If This Be Treason: Translation and Its Dyscontents, and you won’t want to miss the part about him serving as a cryptographer in WWII – surely outstanding preparation for a future translator – nor his really interesting thoughts about, for example, how the sounds of a language can influence the style of translations from that language. “He’s the godfather of us all,” Edith Grossman (herself one of the most revered translators alive) told the Associated Press earlier today. If there’s a translators’ heaven, you can be sure that Constance Garnett, Ralph Manheim, Michael Henry Heim, and William Weaver have saved a seat at the banquet table for him. I’m sure they’ll have a lot to talk about.

Meanwhile if you’d like to take a look at the interview I did with him, you can find it on the website of the The Rumpus. Always charming, always enlightening, and mindbogglingly prolific – he will be missed.