I’m celebrating my birthday in Berlin this year – something I used to do all the time when it was part of my life rhythm to spend summers (all summer, every summer) here. Now the city is changing so much I hardly recognize parts of it, and it is full of Americans the way Prague used to be. In recent years, my life rhythm has changed, and now I generally come to Germany only when I have a specific occasion.  The occasion this summer was being the 2012 recipient of the Calw Hermann Hesse Translation Prize, which included an invitation to participate in a prize ceremony held in Hesse’s birthplace in the Black Forest. Calw is lovely: a little jewel box of half-timbered houses, some of them old and real, some of them “nachempfunden” (“in the sentiment of,” i.e. copies). There are modern touches aplenty, but walking up and down the main drag – which doesn’t take long – definitely gives you a sense of what the town must have felt like a hundred or two hundred years ago. In Calw, Hesse is a major tourist attraction. The Hesse Museum has a large show of his watercolors up, some of which

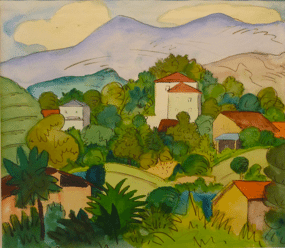

The occasion this summer was being the 2012 recipient of the Calw Hermann Hesse Translation Prize, which included an invitation to participate in a prize ceremony held in Hesse’s birthplace in the Black Forest. Calw is lovely: a little jewel box of half-timbered houses, some of them old and real, some of them “nachempfunden” (“in the sentiment of,” i.e. copies). There are modern touches aplenty, but walking up and down the main drag – which doesn’t take long – definitely gives you a sense of what the town must have felt like a hundred or two hundred years ago. In Calw, Hesse is a major tourist attraction. The Hesse Museum has a large show of his watercolors up, some of which  are quite beautiful. I was taken to see the room where Hesse was born by the building’s current owners, the family that runs the largest clothing store in town. Apparently German rock musician Udo Lindenberg likes to visit this room regularly to commune with Hesse’s spirit; I too sat for a few moments on Lindenberg’s chair. I was even invited to tea for an afternoon of reminiscences by the astonishing Frau Bodamer, daughter of Hesse’s favorite cousin,

are quite beautiful. I was taken to see the room where Hesse was born by the building’s current owners, the family that runs the largest clothing store in town. Apparently German rock musician Udo Lindenberg likes to visit this room regularly to commune with Hesse’s spirit; I too sat for a few moments on Lindenberg’s chair. I was even invited to tea for an afternoon of reminiscences by the astonishing Frau Bodamer, daughter of Hesse’s favorite cousin, who visited Hesse several times in Montagnola as a young girl (and is now a girlish 96); the family resemblance is striking.

who visited Hesse several times in Montagnola as a young girl (and is now a girlish 96); the family resemblance is striking.

I asked every Calwer I met what he or she thought of Hesse’s work, and invariably I received the answer: “I loved him when I was young.” That’s just how it was with me as well. Last winter, when I was told I had been selected for this prize and would have to give a speech about Hesse in German, I thought back on the experience of translating Siddhartha, and realized that my entire relationship to Hesse was based on the fact that this book had meant everything to me at age thirteen. In my junior high school, it was one of the books the “cool kids” were passing around and reading, and since I wanted to be one of them (no, it didn’t work), I got hold of a copy and read it too. I might even have borrowed the book off one of my crushes, C.C., who spent much of that year limping around touchingly on a broken foot. But even apart from the external factors that made the book an object of desire, every line in it seemed designed to speak to the anguish and yearning known to roil the teenage heart. Siddhartha, the young man groping his way through life, trying out one thing after another in search of the perfect existence, perfect peace and perfect knowledge: nirvana – couldn’t we all live like that? I read his story thirstily, doggedly, infatuatedly. I sneaked a few pages under my desk during class. And my reading of the book became infused with all the hopes and fears that accompanied the first inklings of adulthood and its dangers and responsibilities (a classmate of ours got pregnant, for example, and we never saw her again).

Twenty-five years later, when I sat down to translate Siddhartha for Modern Library, all these long-forgotten feelings came flooding back, and several times I found myself weeping at the keyboard as I relived scene after deliciously fraught scene (Siddhartha’s despair, the death of Kamala, the final revelation). I could never have harbored such feelings for this book if I had first encountered it as an adult. But as an adult reader and translator I was able to arrive at a new appreciation of the novel, particularly after having learned more about the circumstances of its composition. Hesse began writing Siddhartha late in 1919, at a time when all of Europe was still reeling from the trauma of the Great War, which had decimated an entire generation of young men. His novel presents a fantasy diametrically opposed to the violence of war: a world in which young men have the leisure to seek out the paths best suited to them. And this is what so excited us in junior high school, at a point in our lives when we were all desperately weary of being told what to do but not yet ready to take on the responsibility for our own lives and learning. I spoke about these things on the stage of the town auditorium in Calw on Hesse’s birthday, July 2. It was a fancy prize ceremony, with local dignitaries galore, a cello ensemble, and an amazing Laudatio by Denis Scheck. You can read his words along with mine on the website of the Calw Hermann Hesse Foundation. Pictures of the ceremony are posted there too.

Congratulations, Susan!

It was a pleasure to read your post.

Sasha