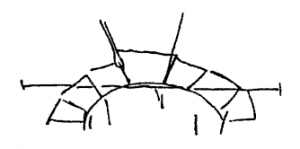

Yesterday I spent several hours with German poet Uljana Wolf – a book of whose poems I’m translating for Ugly Duckling Presse – going over the texts of the poems. This certainly isn’t something I always do with an author whose work I’m translating, but Uljana herself translates from English to German and speaks outstanding English. She also tends to have excellent ideas about navigating the thornier passages in her poems, which is particularly useful in the present case, since the book in question is an abecedary of sorts, each poem inspired by “false friends” or German/English cognates that wind up meaning completely different things in the two languages, and  written in a mix of German and English. The “i” poem, for example, invokes the German word “igel” that appears doubly in English: both as its semantic equivalent “hedgehog” and its homophonic translation “eagle,” which get linked in a semi-narrative passage involving the sorts of animals that figure in fairy tales. In any case, being able to pick Uljana’s brain during the final revision process was invaluable, and certain choice tidbits in the translation are her personal contributions; in the “c” poem, for instance – a sensual take on love – the word “donut” that got deconstructed in the German into “du not go, or i’ll go nuts” (du = you) now reads, in the purely English version, “do nut go, or i’ll go nuts.” It’s a shame that the overtly bilingual character of the poems has to be glossed over in the translation, but the fact of the matter is that while most educated Germans read enough English to understand bilingual poems with ease, making substantial use of German in the translations would limit the poems’ readership dramatically. In any case, while revising we found ourselves swapping phrases back and forth and pinching out individual words and bits of lines that didn’t quite work, replacing them with others. And it invariably happened that the rhythms of these missing building blocks presented themselves before the words themselves could be found, a phenomenon I’ve written about elsewhere. While we were talking about our collaboration afterward, it occurred to us that this way of thinking about the translation process was well described by the great Heinrich von Kleist‘s aphorism: “The arch stands because each of its stones wants to fall.” Kleist described this phenomenon in a letter to his betrothed, Wilhelmine von Zenge, whom he was attempting to educate epistolarily, and even drew a picture to show her what he was talking about:

written in a mix of German and English. The “i” poem, for example, invokes the German word “igel” that appears doubly in English: both as its semantic equivalent “hedgehog” and its homophonic translation “eagle,” which get linked in a semi-narrative passage involving the sorts of animals that figure in fairy tales. In any case, being able to pick Uljana’s brain during the final revision process was invaluable, and certain choice tidbits in the translation are her personal contributions; in the “c” poem, for instance – a sensual take on love – the word “donut” that got deconstructed in the German into “du not go, or i’ll go nuts” (du = you) now reads, in the purely English version, “do nut go, or i’ll go nuts.” It’s a shame that the overtly bilingual character of the poems has to be glossed over in the translation, but the fact of the matter is that while most educated Germans read enough English to understand bilingual poems with ease, making substantial use of German in the translations would limit the poems’ readership dramatically. In any case, while revising we found ourselves swapping phrases back and forth and pinching out individual words and bits of lines that didn’t quite work, replacing them with others. And it invariably happened that the rhythms of these missing building blocks presented themselves before the words themselves could be found, a phenomenon I’ve written about elsewhere. While we were talking about our collaboration afterward, it occurred to us that this way of thinking about the translation process was well described by the great Heinrich von Kleist‘s aphorism: “The arch stands because each of its stones wants to fall.” Kleist described this phenomenon in a letter to his betrothed, Wilhelmine von Zenge, whom he was attempting to educate epistolarily, and even drew a picture to show her what he was talking about: The point of the arch was to serve as an allegorical symbol of human fortitude in the face of trials. Kleist recycled the image eight years later in his play Penthesilea, in which a consort of the beleaguered Amazon queen uses a quite similar phrase to encourage her regent to buck up. In any case, something in our conversation reminded me of this image, and when I quoted it, Uljana pointed out that it also described the very activity we’d been pursuing all afternoon: trying to find just the right combination of (individually fallible and failing) words that would prop each other up to hold the lines of poetry together. If you are curious to see the results of our efforts, I’m afraid you’ll have to wait until approximately April for the appearance of our book False Friends: A DICHTionary of False Friends, True Cognates and Other Cousins, by Uljana Wolf. I’m sure we’ll be throwing a nice book party when the time comes, so watch this space for details.

The point of the arch was to serve as an allegorical symbol of human fortitude in the face of trials. Kleist recycled the image eight years later in his play Penthesilea, in which a consort of the beleaguered Amazon queen uses a quite similar phrase to encourage her regent to buck up. In any case, something in our conversation reminded me of this image, and when I quoted it, Uljana pointed out that it also described the very activity we’d been pursuing all afternoon: trying to find just the right combination of (individually fallible and failing) words that would prop each other up to hold the lines of poetry together. If you are curious to see the results of our efforts, I’m afraid you’ll have to wait until approximately April for the appearance of our book False Friends: A DICHTionary of False Friends, True Cognates and Other Cousins, by Uljana Wolf. I’m sure we’ll be throwing a nice book party when the time comes, so watch this space for details.

(Photo of Uljana Wolf © Timm Kolln)

Susan Bernofsky

New York, NY

New York, NY

Writer and translator Susan Bernofsky loves to blog about all things translation. Click here to find her on Twitter.

Most Popular Posts

- Getting the Rights to Translate a Work: A How-To Guide

- Friedrich Schleiermacher

- Tips for Beginning Translators

- Magazines That Publish Translations

- Rules for Translators

- Remembering William Weaver (1923 – 2013)

- How to Review Translations

- Saying Goodbye to Michael Henry Heim (1943 – 2012)

- The Three Percent Problem

- A Tour of the NYPL Stacks

Blogroll

- ALTA blog

- American Literary Translators Association (ALTA)

- Arabic Literature (in English)

- Archipelago

- Asymptote

- Authors & Translators

- Autumn Hill Books

- Biblibio

- Bookaccino

- Cardinal Points

- Center for the Art of Translation

- FR (Frederika Randall)

- Global Literature in Libraries Initiative

- Host

- InTranslation

- Love German Books

- New Directions

- New Vessel Press

- Open Letter

- PEN America

- Reader at Large

- Reading in Translation

- Sunshine Abroad (Allison M. Charette)

- Three Percent

- Trafika Europe

- Transit Books

- Translating Women

- Translation Tribulations

- Two Lines

- Ugly Duckling

- Women in Translation

- Words Without Borders

- Zephyr Press

January 17th, 2011

The Architecture of Translation

Comments are closed.

Recent Posts

Blog Archive

- ►2024 (1)

- ►2022 (4)

- ►2021 (1)

- ►2020 (5)

- ►2019 (74)

- ► December (5)

- ► November (5)

- ► October (5)

- ► September (4)

- ► August (3)

- ► July (5)

- ► June (3)

- ► May (11)

- 2019 Firecracker Award Shortlists Announced

- 2019 Best Translated Book Awards Announced

- A Memory of Gregory Rabassa (1922 – 2016)

- Translation on Tap in NYC, June 1 - 30, 2019

- Submit Now for Words Without Borders Poems in Translation Contest

- 2019 Man Booker International Prize Announced

- 2019 French-American Foundation Translation Prize Announced

- Apply Now for a 2020 PEN/Heim Translation Fund Grant

- 2019 Gutekunst Prize Announced

- 2019 Best Translated Book Award Shortlists Announced

- 2019 Helen and Kurt Wolff Prize Announced

- ► April (15)

- 2019 NSW Premier’s Translation Prize Announced

- 2019 Pushkin House Russian Book Prize Shortlist Announced

- Translated Works Among 2019 Will Eisner Comic Industry Award Nominees

- Translation on Tap in NYC, May 1 - 31, 2019

- 2019 French Voices Awards Announced

- Saying Goodbye to Donald Keene (1922 - 2019)

- Frankfurt International Translators Programme 2019: Apply Now

- 2019 Helen and Kurt Wolff Prize Shortlist Announced

- 2019 Best Translated Book Award Longlists Announced

- 2019 Man Booker International Prize Shortlist Announced

- 2019 Griffin Poetry Prize Shortlist Announced

- 2019 International DUBLIN Literary Award Shortlist Announced

- 2019 Albertine Prize Shortlist Announced - Vote Now!

- Job Opening at ALTA (American Literary Translators Association)

- Apply Now to be Fall 2019 or Spring 2020 Translator-in-Residence at Princeton University

- ► March (6)

- ► February (5)

- ► January (7)

- Shortlists Announced for 2019 PEN Translation Prizes

- 2019 Batchelder Award Announced

- Children's Books in Translation

- Apply Now To Translate in Banff in Summer 2019

- 2019 Close Approximations Translation Prizes Announced

- 2018 Society of Authors Translation Prize Shortlists Announced

- 2018 Kyoko Selden Memorial Translation Prize Announced

- ►2018 (95)

- ► December (6)

- ► November (7)

- Translation on Tap in NYC, Dec. 1 - 31, 2018

- 2019 International DUBLIN Literary Award Longlist Announced

- New Literature from Europe Festival 2018

- 2018 National Book Award for Translated Literature Announced

- 2018 Warwick Prize for Women in Translation Announced

- 2018 Warwick Prize for Women in Translation Shortlist Announced

- 2018 ALTA Translation Prizes Announced

- ► October (8)

- Submit Now: 2018-2019 Geisteswissenschaften International Nonfiction Translators Prize

- Translation on Tap in NYC, Nov. 1 - 30, 2018

- Saying Goodbye to Anthea Bell

- Apply Now to be 2019 Translator-in-Residence at Princeton University

- 2018 National Book Award for Translated Literature Shortlist Announced

- 2018 Warwick Prize for Women in Translation Longlist Announced

- 2018 ALTA Fellows Announced

- 2018 Italian Prose in Translation Award Shortlist Announced

- ► September (7)

- Translation on Tap in NYC, Oct. 1 - 31, 2018

- Happy International Translation Day 2018!

- 2018 Etxepare-Laboral Kutxa Translation Prize Announced

- 2018 National Book Award for Translated Literature Longlist Announced

- 2018 Lucien Stryk Asian Translation Prize Shortlist Announced

- Register Now for "Translation Now" Symposium at Boston University

- 2018 National Translation Award Shortlists Announced

- ► August (7)

- NEA Announces 2019 Translation Fellowships

- Academy of American Poets 2018 Translation Prizes Announced

- Translation on Tap in NYC, September 1 - 30, 2018

- Submit Now for Asymptote’s 2019 Close Approximations Translation Prize

- WeTransist

- Women in Translation Month 2018

- 2018 French-American Foundation Translation Prize Announced

- ► July (7)

- Translation on Tap in NYC, Aug. 1 - 31, 2018

- Apply Now for the Harvill Secker Young Translators’ Prize

- Kate Briggs, "This Little Art"

- Translator's Discount, Willamette Writers Conference

- 2018 National Translation Award Longlists Announced

- Submit Now for the 2019 TA First Translation Prize

- Fall 2018 PEN Translates Awards Announced

- ► June (8)

- Translation on Tap in NYC, July 1 - 31, 2018

- Words Without Borders Wins Inaugural Whiting Magazine Prize

- 2018 Transatlantyk Prize Announced

- Inaugural World Literature Today Translation Prize Announced

- 2018 Oxford-Weidenfeld Translation Prize Announced

- 2018 Albertine Prize Announced

- 2018 Best Translated Book Awards Announced

- Submit Now: Warwick Prize for Women in Translation

- ► May (8)

- Translation on Tap in NYC June 1 - 30, 2018

- 2018 Gutekunst Prize Announced

- 2018 Man Booker International Prize Announced

- Open Call for Submissions: Señal

- 2018 Best Translated Book Award Shortlists Announced

- 2018 Helen and Kurt Wolff Prize Announced

- 2018 Oxford-Weidenfeld Translation Prize Shortlist Announced

- Study Translation at Columbia This Summer

- ► April (10)

- Translation on Tap in NYC, May 1 - 31, 2018

- 2018 Straelen Translator's Prize Announced

- 2018 Man Booker International Prize Shortlist Announced

- 2018 Helen and Kurt Wolff Prize Shortlist Announced

- 2017 French Voices Awards Announced

- 2018 Best Translated Book Award Longlists Announced

- 2018 Guggenheim Fellowship in Translation to Esther Allen

- Free 2018 One-Day Literary Translation Institute at Long Island University in Brooklyn

- 2018 Found in Translation Award Announced

- 2018 Dublin Literary Award Shortlist Announced

- ► March (9)

- Translation on Tap in NYC, April 1 - 30, 2018

- Apply Now for a 2018 ALTA Travel Fellowship

- 2018 American Academy of Arts and Letters Awards Announced

- Donald Keene Center of Japanese Culture Awards 2017-2018 Translation Prizes

- French-American Foundation Translation Prize 2018 Shortlists Announced

- 2018 Man Booker International Prize Longlist Announced

- 2018 Soeurette Diehl Fraser Award Announced

- 2017 Society of Authors Translation Prizes Announced

- TA First Translation Prize Announced

- ► February (9)

- Translation on Tap in NYC, March 1 - 31, 2018

- 2018 PEN Translation Prize Announced

- 2017 Global Humanities Translation Prize Announced

- 2018 PEN/Heim Translation Fund Winners

- 2018 PEN/Ralph Manheim Medal to Barbara Harshav

- Apply Now for Goethe-Institut Translator's Residencies in Germany

- Apply Now for 2018 Translation Lab at Ledig House

- Apply Now To Translate in Banff in Summer 2018

- Apply Now: Modern Greek Translation Workshop at Princeton

- ► January (9)

- National Book Foundation Announces a National Book Award for Translated Literature

- 2017 Gulf Coast Prize in Translation Announced

- Translation on Tap in NYC, Feb. 1 - 28, 2018

- 2018 PEN Translation Prize Shortlist Announced

- Apply Now for American-Scandinavian Translation Awards

- Apply Now for 2018 Gutekunst Prize

- TA First Translation Prize Shortlist Announced

- Introducing The Queer Translation Collective

- 2017 Modern Language Association Translation Prizes Awarded

- ►2017 (101)

- ► December (6)

- Translation on Tap in NYC, Jan. 1 - 31, 2018

- 2018 PEN Translation Prize Longlist Announced

- 2017 Authors Guild Survey of Literary Translators’ Working Conditions

- Princeton Names Its First Translator in Residence

- Apply Now for the 2018 Straelener Übersetzerpreis der Kunststiftung NRW

- Shortlist Announced / Voting Open for 2018 Albertine Prize

- ► November (8)

- Translate at Bread Loaf in Summer 2018

- Translation on Tap in NYC Dec. 1 - 31, 2017

- 2017 French-American Foundation Translation Prize Winners Announced

- 2017 Stephen Spender Prize for Poetry in Translation Announced

- NEA Announces 2018 Translation Fellowships

- 2017 Warwick Prize for Women in Translation Announced

- Fall 2017 PEN Translates Awards Announced

- 2018 Dublin Literary Award Longlist Announced

- ► October (10)

- Translation on Tap in NYC, Nov. 1 - 30, 2017

- Translators/Translation Curators Sought for Transgender Studies Quarterly

- Apply Now to Be a Translator-in-Residence at the University of Iowa

- Want To Be the First Ever Translator-in-Residence at Princeton? Apply now!

- Apply Now for TRANSLAB Workshop for German-language Nonfiction

- 2017 Warwick Prize for Women in Translation Shortlist Announced

- 2017 PEN Center USA Translation Award Announced

- 2017 ALTA Awards Announced

- American Academy of Poets Announces New Translation Prize

- Translation on Tap in NYC, Oct. 1 - 31, 2017

- ► September (4)

- ► August (6)

- ► July (6)

- ► June (9)

- Translation on Tap in NYC July 1 - 31, 2017

- Anomaly Now Open for Submissions

- 2017 National Translation Award Longlists Announced

- Translated Book on Shortlist for 2017 Palestine Book Awards

- 2017 International DUBLIN Literary Award Announced

- Submit Now for the 2017 Gulf Coast Prize in Translation

- 2017 Man Booker International Prize Announced

- 2017 Austrian Cultural Forum New York Translation Prize Announced

- 2017 Firecracker Award in Fiction Goes to a Translated Book

- ► May (7)

- Free One-Day Literary Translation Institute at Long Island University in Brooklyn

- Translation on Tap in NYC, June 1 - 30, 2017

- 2017 Firecracker Award Shortlists Announced

- 2017 Albertine Prize Announced

- 2017 Gutekunst Prize Announced

- 2017 Best Translated Book Awards Announced

- Submit Now: Two Competitions for Translators from Japanese

- ► April (12)

- Apply Now for a 2017 ALTA Emerging Translator Mentorship

- 2017 Helen and Kurt Wolff Prize Announced

- Translation on Tap in NYC, May 1 - 31, 2017

- 2017 Man Booker International Shortlist Announced

- 2017 Best Translated Book Award Shortlists Announced

- 2017 Helen and Kurt Wolff Prize Shortlist Announced

- Shortlist / Round Two Voting Open for 2017 Albertine Prize

- Remembering Burton Watson (1925 - 2017)

- Translation at the 2017 PEN World Voices Festival

- 2017 International DUBLIN Literary Award Shortlist Announced

- Translation on Tap in NYC, April 16 - 30, 2017

- 2016 French Voices Awards Announced

- ► March (12)

- New Global Humanities Translation Prize Announced

- 2016 Gulf Coast Translation Prize Winner Announced

- 2017 Best Translated Book Award Longlists Announced

- Translation on Tap in NYC, April 1 - 15, 2017

- French-American Foundation Translation Prize 2017 Shortlists Announced

- What I'm Reading: Scholastique Mukasonga

- Vote Now for 2017 Albertine Prize

- Apply Now for 2017 Translation Lab at Ledig House

- 2017 Man Booker International Longlist Announced

- Apply Now for an ALTA Travel Fellowship

- Announcing the Warwick Prize for Women in Translation

- Translate at Bread Loaf in Summer 2017

- ► February (10)

- Translation on Tap, March 1 - 31, 2017

- Festival Neue Literatur 2017

- 2017 PEN Translation Awards Announced

- Submit Now for 2017 Gabo Prize for Literature in Translation & Multilingual Texts

- Translation on Tap in NYC, Feb. 15 - 28, 2017

- Apply Now for the 6th Biennial Graduate Translation Conference

- Translation Events at AWP 2017

- 2017 PEN/Heim Translation Fund Winners

- Getting the Rights to Translate a Work: A How-To Guide

- Submit Now for Epiphany Magazine's 2017 Translation Contest

- ► January (11)

- A Joint Statement on the Executive Order Restricting Immigrant and Refugee Entry into the US

- Translation on Tap in NYC, Feb. 1 - 15, 2017

- Submit Now for Asymptote's 2017 Close Approximations Translation Prize

- Finalists Announced for 2017 PEN Translation Prizes

- Translation on Tap in NYC, Jan. 16 - 31, 2017

- Apply Now for 2017 Gutekunst Prize

- Apply Now for German-English Translation Workshop at Ledig House

- 2017 German Nonfiction Translation Competition Award Announced

- 2016 Saif Ghobash Banipal Prize for Arabic Literary Translation

- Apply Now for the Graduate Student Conference on Translation and Translation Studies

- Translation on Tap in NYC, Jan. 1 - 15, 2017

- ► December (6)

- ►2016 (81)

- ► December (3)

- ► November (3)

- ► October (4)

- ► September (4)

- ► August (9)

- Translation on Tap in NYC, Sept. 1 - 30, 2016

- Apply Now for the Helen Hammer Translation Prize

- 2016 PEN Center USA Translation Award Announced

- NEA Announces 2017 Translation Fellowships

- Words Without Borders's Women in Translation Month Recommended Reads

- Jen Campbell's Women in Translation Month Recommendations

- 2016 National Translation Award Longlists Announced

- Translation on Tap in NYC Aug. 1 - 31, 2016

- Read These Women in Translation Now!

- ► July (5)

- ► June (4)

- ► May (14)

- Translation on Tap in NYC, June 1 - 30, 2016

- 2016 Shortlists Announced, French-American Foundation Translation Prize

- 2016 Helen and Kurt Wolff Prize and Gutekunst Prize Announced

- Apply Now for the 2017 Austrian Cultural Forum Translation Prize

- 2016 Firecracker Award in Fiction Goes to a Translated Book

- Apply Now for the 2016 Global Humanities Translation Prize

- Translate in London This July

- 2016 Oxford-Weidenfeld Translation Prize Shortlist Announced

- Submit Now for the 2017 Cliff Becker Book Prize in Translation

- 2016 Man Booker International Prize Announced

- Translation on Tap in NYC, May 16 – 31, 2016

- 2016 Best Translated Book Award Winners Announced

- Why Translating Black Writers Matters

- Translation on Tap in NYC, May 1 - 15, 2016

- ► April (11)

- Translate at Bread Loaf in Summer 2016

- Report on the Bridge Series's Contracts panel

- 2016 Best Translated Book Award Finalists Announced

- Soeurette Diehl Fraser Award for Best Translation Announced

- Apply Now for a 2016 ALTA Emerging Translator Mentorship

- 2016 Close Approximations Winners Announced

- 2016 Dublin, Man Booker International Shortlists Announced

- London Book Fair/Publishers Weekly Literary Translation Initiative Award Announced

- Translation on Tap in NYC, April 16 - 30, 2016

- Subscribe to Literature in Translation

- Apply Now to Become a 2016 ALTA Fellow

- ► March (9)

- CLMP Shortlists Four Translated Books for 2016 Firecracker Awards

- Best Translated Book Award 2016 Poetry Longlist

- Best Translated Book Award 2016 Fiction Longlist

- Translation Panels at AWP 2016

- Translation on Tap in NYC, April 1 - 15, 2016

- Translation on Tap in NYC, March 16 - 31, 2016

- Apply Now for a Peter K. Jansen Memorial Travel Fellowship to Attend ALTA

- 2016 Man Booker International Longlist Announced

- 2016 PEN Translation Awards Announced

- ► February (7)

- ► January (8)

- Translation on Tap in NYC, Feb. 1 - 15, 2016

- Apply Now for 2016 Gutekunst Prize

- 2015 AATSEEL Translation Award Announced

- 2016 Cliff Becker Prize Announced

- Apply Now for 2016 Translation Lab at Ledig House

- Apply Now for the 2016 French-American Foundation Translation Prize

- Apply Now To Translate in Banff This Summer

- Translation on Tap in NYC, Jan. 1 - 31, 2016

- ►2015 (91)

- ► December (5)

- ► November (4)

- ► October (9)

- 2015 ALTA Prizes Announced

- 2015 Italian Prose in Translation Award Shortlist

- Translation on Tap in NYC, Nov. 1 - 15, 2015

- Who's Getting Translated? Mostly Men

- Amazon to Spend $10,000,000 on Translation

- Apply Now for a 2016 PEN/Heim Translation Fund Grant

- Translation on Tap in NYC, Oct. 15 - 31, 2015

- 2015 National Translation Award Shortlists Announced

- Vote for Your Favorite Work in Translation Supported by English PEN

- ► September (8)

- Goodmorning Menagerie's 2nd Annual Chapbook Translation Prize

- Translation on Tap in NYC, Oct. 1 - 15, 2015

- 2015 ALTA Mentorships Announced

- 2015 Harold Morton Landon Translation Award Announced

- 2015 ALTA Fellows Announced

- 2015 PEN Center USA Translation Award Announced

- Translation on Tap in NYC, Sept. 16 - 30, 2015

- Call for Nominations: Italian Prose in Translation Award

- ► August (7)

- Translation on Tap in NYC, Sept. 1 - 15, 2015

- Read Kafka with Translationista at the 92nd St. Y

- Remembering Carol Brown Janeway

- Translators: Join the Author's Guild by Aug. 31 for a Discount

- Translation on Tap in NYC, Aug. 16 - 31, 2015

- NEA Announces 2016 Translation Fellowships

- Submit Now for Close Approximations, Asymptote's Translation Prize

- ► July (5)

- ► June (3)

- ► May (16)

- 2015 Read Russia Prize Announced

- 2015 PEN/Heim Translation Fund Winners

- 2015 Best Translated Book Award Winners

- Translation on Tap in NYC, June 1 - 15, 2015

- 2015 Oxford-Weidenfeld Translation Prize Shortlist

- Apply Now to Become a 2015 ALTA Fellow

- 2015 PEN Translation Prizes Announced

- Translation on Tap in NYC, May 16 - 31, 2015

- Translation at BEA 2015

- Talking Translation at the 2015 PEN World Voices Festival: Bloggers and the Slam

- Talking Translation at the 2015 PEN World Voices Festival: Women's Voices

- 2015 Helen and Kurt Wolff Prize to Catherine Schelbert

- 2015 Ralph Manheim Medal to Burton Watson

- 2015 Gutekunst Prize to Sophie Duvernoy

- Best Translated Book Award 2015 Shortlists

- Why I Signed the PEN Protest Letter

- ► April (13)

- 2015 French-American Foundation Translation Prize Finalists

- Translation on Tap in NYC, May 1 – 15, 2015

- Remembering Benjamin Harshav, 1928-2015

- Translation at the 2015 London Book Fair

- Translation at the 2015 PEN World Voices Festival

- Translation in Transition Conference, May 1-2, 2015

- New Spaces of Translation: A Reportback

- Translation Shortlists, Spring 2015

- Translation on Tap in NYC, April 16 - 30, 2015

- Where Are the Women in Translation?

- Best Translated Book Award 2015 Longlists

- What Should Translators Get Paid for Their Work?

- Translation Panels at AWP 2015

- ► March (4)

- ► February (9)

- Writers Translating Writers

- Apply Now for 2015 Gutekunst Prize

- Translation on Tap in NYC, March 1 – 15, 2015

- Translate with Translationista at Bread Loaf

- Monique Truong on the Art of Translation

- Festival Neue Literatur 2015

- Translation on Tap in NYC, Feb. 16 – 28, 2015

- Time to Apply to Translate in Banff!

- Translation on Tap in NYC, Feb. 1 – 15, 2015

- ► January (8)

- Apply Now for the 2015 French-American Foundation Translation Prize

- 2015 Austrian Cultural Forum Translation Prize Announced

- Apply Now for a 2015 PEN/Heim Translation Fund Grant

- Translation on Tap in NYC, Jan. 16 - 31, 2015

- An Officer and a Translator

- Apply now for the 5th Biannual Graduate Student Translation Conference

- Translation on Tap in NYC, Jan. 1 – 15, 2015

- Translation at the 2015 MLA

- ►2014 (94)

- ► December (5)

- ► November (4)

- ► October (9)

- Translation on Tap in NYC, Nov. 1 – 15, 2014

- Transgender Translation Studies

- Goodmorning Menagerie Translation Chapbook Contest

- Speed-Date an Editor at the ALTA Conference

- Magazines That Publish Translations

- Translators Fighting Ebola

- Translation on Tap in NYC, October 16 – 31, 2014

- Translation Symposium in Louisville, Oct. 16-17, 2014

- My Coffee with Wally

- ► September (7)

- ► August (9)

- PEN Center USA 2014 Translation Award Announced

- Gulf Coast Translation Prize Deadline Aug. 31

- Translation on Tap in NYC September 1 – 15, 2014

- Sept. 19 Symposium at the Nida School of Translation Studies

- The Translator as Heroine (Xiaolu Guo in NYC)

- Win a Kafka Audiobook

- 2014 PEN/Heim Translation Fund Grants Announced

- NEA Announces 2015 Translation Fellowships

- 2014 National Translation Award Longlist Announced

- ► July (3)

- ► June (11)

- Speaking English in Malaysia

- Apply Now to Become a 2014 ALTA Fellow

- Translationista on Hiatus

- 2014 IMPAC Dublin Award Announced

- World Cup of Literature

- Translation on Tap in NYC June 16 - 22, 2014

- The Austrian Cultural Forum Translation Prize Is Back

- 2014 Compass Award Competition for Russian Poetry

- Absinthe Moves to University of Michigan

- Translation on Tap in NYC June 9 - 15, 2014

- A Few More NYSCA Pointers As Deadline Approaches

- ► May (18)

- 2014 Independent Foreign Fiction Prize to Jonathan Wright

- 2014 Oxford Weidenfeld Translation Prize Shortlist / Oxford Translation Day

- Translation on Tap in NYC May 26 - June 1

- Translation at Book Expo America 2014

- Translating for the Stage

- 2014 Gutekunst Prize to Elisabeth Lauffer

- 2014 French-American Foundation Translation Prizes Announced

- Translating The Magic Flute

- French Translators Protest Amazon Contracts

- Questionnaires - Max Frisch and Me

- Rosie Goldsmith's 2014 Top Five Translated Books

- Translation on Tap in NYC May 12-18, 2014

- A Library Without Books?

- NYPL Drops Central Library Plan

- PEN Translation Prize Linguists 2014

- Matchmaking Service for Translators, Publishers?

- Robert Walser at the Elizabeth Street Garden

- 2014 Wolff Prize to Shelley Frisch

- ► April (10)

- 2014 Best Translated Book Award Winners Announced

- Translation on Tap in NYC May 5 - 11, 2014

- Translationista Has a New Look

- International Books and Roses Day 2014

- Crossing Worlds Conference, May 2-3, 2014

- Translation on Tap in NYC April 26 - May 3, 2014

- Translation Events at 2014 PEN World Voices Festival

- Best Translated Book Award 2014 Shortlists

- 2014 Independent Foreign Fiction Prize Shortlist Announced

- Best Translated Book Award Wins New London Book Fair Prize

- ► March (8)

- ► February (6)

- ► January (4)

- ►2013 (79)

- ► December (5)

- ► November (3)

- ► October (12)

- This Week in Translation Starts Tonight!

- Who's Afraid of Spiders?

- When Translators Get Shafted

- ALTA Translation Prizes 2013

- ALTA 2013 Part 3: Advocacy and Promotion

- ALTA 2013 Part 2: Publishing and Funding News

- ALTA 2013 Part 1: Cole Swensen

- TLhub: A Preview of the Future?

- Translation à la McSweeney's

- Translation on Tap in NYC Next Week

- Found in Translation and Other Events This Week

- Library Update

- ► September (7)

- ► August (5)

- ► July (4)

- ► June (8)

- Saving the New York Public Library

- A Library for the People

- Apply for Translation Lab at Ledig House

- French-American Translation Prize Winners 2013

- New Bridge = German Quartet

- Reminder: Launch for In Translation Tomorrow

- French-American Translation Prize Ceremony Tomorrow

- Talking Translation at Book Expo America

- ► May (6)

- ► April (17)

- What I Learned at the 2013 London Book Fair

- Siri Hustvedt on Authors & Translators Blog

- A Master Class with Michael Emmerich

- Translation Events at 2013 PEN World Voices Festival

- How To Be a Translator - Translationista at PWV2013

- Cyprus, Divided Cities, and Translation Studies

- Medvedev & Gessen at Columbia on Wednesday

- What I Learned at the HotINK/PEN Translation Panel

- Turkish Bridge!

- The Politics of Polyglossia May 6

- HotINK Festival of International Plays on NOW

- Translating Lorca at the Lorca Festival

- Best Translated Book Award 2013 Finalists

- Marian Schwartz and Mikhail Shishkin Tomorrow

- Ritsos And His Translators Tonight

- Borges at the Americas Society on April 8

- Tonight tonight! Harry Mathews and Marie Chaix

- ► March (4)

- ► February (4)

- ► January (4)

- ►2012 (74)

- ► December (5)

- ► November (9)

- Fuentes's Translators Take the Stage

- English PEN Announces 2012 Translation Awards

- Submit to Asymptote

- Got International Flash Fiction? Submit Here!

- Now with Moderated Comments

- Mario Vargas Llosa and Edith Grossman tonight!

- Remembering Nancy Festinger

- Remembering Nancy Festinger / Esther Allen

- Remembering Nancy Festinger / Jim Kates

- ► October (11)

- Two Commonplaces: News from ALTA

- Please Support Words Without Borders

- Translation On Tap in NYC Next Week

- On Publishers Boycotting Translation Prizes

- Michael Henry Heim in the Classroom

- Double Translation Night This Wednesday

- Translation Night at the AAWW

- Recruiting for the Reviewer Hall of Fame

- Peter Bush Speaks at Baruch

- Looks Like It's ALTA Time

- PEN Translation Fund Donor's Identity Revealed

- ► September (8)

- Saying Goodbye to Michael Henry Heim (1943 - 2012)

- Happy International Translation Day

- German Book Office Contest for Aspiring Translators

- PEN Translation Committee at the Brooklyn Book Festival

- Book Party for PEN Translation Fund Recipient Nathanaël

- Friday: Translation Night Out

- Viva Rabassa

- English to English Translation

- ► August (4)

- ► July (3)

- ► June (2)

- ► May (9)

- ► April (5)

- ► March (7)

- ► February (2)

- ► January (9)

- Book Party for Berlin Stories Feb. 2

- Attn. Portuguese Translators: 2012 Susan Sontag Prize

- PEN Translation Fund Deadline Feb. 1

- Banff Centre Deadline Feb. 15

- Young Translators at ALTA

- Thinking about Berlin Stories

- Michael Henry Heim in Boston

- William Carlos Williams, Translator

- Study with Edith Grossman in NYC!

- ►2011 (105)

- ► December (4)

- ► November (4)

- ► October (7)

- ► September (10)

- The Revolution Will Be Translated

- G.J. Racz at Americas Society Tonight

- Generation Telephone?

- Onesies and Twosies at the Brooklyn Book Festival

- Translators at the Brooklyn Book Festival

- The Three Percent Problem

- Blogging for PEN

- The Next Bridge is El Puente

- 9/11, a Translator's View

- The Translator's Playbook

- ► August (4)

- ► July (12)

- Translationista Action Figure

- Last PEN Online Translation Slam = Korean!

- 2012 NEA Translation Fellowships Announced

- Guest blogging at Women and Hollywood

- Mónica de la Torre Translating Herself

- 2011 PEN Translation Fund Winners Announced

- The Elephant Woman

- Happy Birthday New Directions!

- Iranian Copyright

- Trial Continues for Turkish Translator

- Turkish Translator Charged with Obscenity

- NBCC Stands Up for Translation

- ► June (6)

- ► May (10)

- Science Fiction & Fantasy Translation Awards

- Apply Now for Vermont Studio Center Residency

- Edith Grossman honored with 2011 Independent Foreign Fiction Prize

- Poets Translating Poetry

- New Russian Poetry Translation Contest

- Translation Extravaganza Tonight

- Favorite Authors or Favorite Translators?

- Everything You Always Wanted to Know about Copyright and Contracts

- Indie Booksellers Choice Awards Finalists

- Tibetan Literature Comes to You

- ► April (12)

- 2011 Best Translated Book Awards Announced

- What I Found in Translation at the Guggenheim

- An Abecedarian

- Translation at the PEN World Voices Festival

- MLA Embraces Translation as Scholarship

- Guggenheim Forum on Translation

- Independent Foreign Fiction Prize 2011

- Is Greek Poetry All Greek to You?

- Un/Translatables Conference at U Penn

- A Postscript on Independent Publishers

- Visitation Longlisted for an Indie Booksellers Choice Award

- Reading with My Hero

- ► March (12)

- How to Review Translations

- Visitation is a 2011 BTBA Finalist!

- J. Hillis Miller on Benjamin on Translation (cont'd)

- Translator for a Day: A Workshop for Beginners

- Lecture: On the Translations of Lorca

- J. Hillis Miller on Benjamin on Translation

- Translators Love Libraries

- Lush Breezes

- Do You Speak Tranglish?

- So What Is 'Voice' Anyhow?

- What I Learned at Bridge #1

- 2011 PEN World Voices Festival, New York

- ► February (13)

- Bridge Series Launches in NYC

- Big Fellowships to Attend ALTA

- Featured on NPR!

- Announcing the QUILL Translation Award

- Queens in Love with Literature (QUILL)

- Queens College MFA Deadline Now March 1

- Festival Neue Literatur This Weekend!

- When Translators Do Math

- Russian Poetry and Self-Translation

- Friedrich Schleiermacher

- Translation at the AWP

- A Translated Book is Amazon's Current Bestseller

- A Beautiful New Review of Visitation

- ► January (11)

- Computer Programming and Translation

- Bilingualism in the Kitchen

- New Directions Tops the Best Translated Book Award 2011 Fiction Longlist

- When Book Reviewers Ignore Translators

- Talking Translation at Ugly Duckling

- Festival Neue Literatur

- The Architecture of Translation

- Collaborative translation = phone sex?

- Retranslating the German Classics

- Translation and Procrastination

- The Language for the 2011 Sontag Prize? Italian!

- ►2010 (36)

- ► December (19)

- NPR Features Translation as Artistic Partnership

- Translation and Intimacy

- Christmas Rebus

- Robert Walser Died on Christmas Day

- Guest-blogging at Words Without Borders

- Two Three More "Best-of-2010" Listings

- 2010 Aldo and Jeanne Scaglione Prize Goes to Breon Mitchell

- Banff International Literary Translation Centre Now Accepting Applications

- Christian Hawkey's Beating Heart

- Two Translation Awards from the Academy of American Poets

- Translation and Memory

- Two New Reviews of Visitation

- Translationista Under Construction Today

- Translationista Turns One (Month)

- Translation Challenge of the Day: Eiweiß

- Reading at Unnameable Books in Brooklyn, Thursday Dec. 9

- The FT Picks Visitation

- Paris: A Translator’s-Eye View

- Thank you John Ashbery

- ► November (17)

- Queens College MFA Program Open House Dec. 7

- New Translation Prize for Japanese, Dec. 1 Deadline

- Paris, Ho!

- Inventory - A New Journal of Translation

- A Dialogue about Translation (in German)

- Rave Reviews for Visitation

- Ammiel Alcalay Recommends Translating Responsibly

- What Do Translators Like to Read?

- Translator, Meet Thy Author!

- Presenting the American Literary Translators Association

- Why You Should Apply for a PEN Translation Fund Award

- Peter Cole on Translation and Silence

- PEN Online Translation Slam

- Susan Sontag Translation Prize Seminar

- MFA Programs in Creative Writing and Literary Translation

- A New Prize for Young Translators from the German

- A blog about translation

- ► December (19)