I couldn’t believe it when I got offered a chance to do a retranslation of Franz Kafka’s immortal tale of filial angst and degradation, The Metamorphosis. It’s been one of my favorite stories since I first read it as a high school student: the terror of grotesque self-discovery, the sadness, the alienation, that unforgettable image of an apple violently embedded in a back that had at first seemed hard as armor and now was mysteriously penetrable. I read it again, in German this time, as a college student, and then many times thereafter, often in the classroom, shepherding groups of intermediate-level German students through its pages and basking vicariously in the thrill they were experiencing at being able to use their hard-won language skills to enjoy something so spectacular. Kafka’s German is stunning. It’s deceptively straightforward, and this is how he manages to pull off the feat of making utterly implausible occurrences (young man wakes up one morning as a giant bug – WTF?) seem somehow possible and real, at least psychologically real. He’s a master of suspended disbelief. We’ve all had dreams in which the strangest transformations occur, making it easy enough to imagine what it would be like to experience a metamorphosis in real life.

I couldn’t believe it when I got offered a chance to do a retranslation of Franz Kafka’s immortal tale of filial angst and degradation, The Metamorphosis. It’s been one of my favorite stories since I first read it as a high school student: the terror of grotesque self-discovery, the sadness, the alienation, that unforgettable image of an apple violently embedded in a back that had at first seemed hard as armor and now was mysteriously penetrable. I read it again, in German this time, as a college student, and then many times thereafter, often in the classroom, shepherding groups of intermediate-level German students through its pages and basking vicariously in the thrill they were experiencing at being able to use their hard-won language skills to enjoy something so spectacular. Kafka’s German is stunning. It’s deceptively straightforward, and this is how he manages to pull off the feat of making utterly implausible occurrences (young man wakes up one morning as a giant bug – WTF?) seem somehow possible and real, at least psychologically real. He’s a master of suspended disbelief. We’ve all had dreams in which the strangest transformations occur, making it easy enough to imagine what it would be like to experience a metamorphosis in real life.

|

| Photo © Bill Martin 2014 |

And what do you know, the story turns out to be hard to translate. I’m not even going to talk about dealing with that storied word Ungeziefer in the story’s opening line. I’ve got some remarks on that in my translator’s afterword, which was published this week on the New Yorker‘s blog Page-Turner. I assume that anyone who reviews the book is going to have something to say about this; and I’m relieved that the first reviewer to weigh in approved of my solution. But in general the things that give translators the most trouble are not always the most obvious quagmires. In the case of this first sentence, the thing I probably wrestled with the most was trying to find the right place in the sentence to fit the harmless little prepositional phrase “in his bed.” I tried it everywhere I could think of, and, maddeningly, it just didn’t fit. The German language is hospitable to sentences packed with more clauses and phrases than are typical of English prose, so this sort of thing comes up a lot. As a German-English translator, you get used to juggling parts of a sentence around all different ways in search of a configuration in which it won’t be too noticeable how many different moving parts you’ve actually crammed in there. But in this case, I got to thinking about why Kafka included the location tag in the first place. I mean: Gregor just woke up – where else would he be but in his bed? Why is this even worth mentioning? Then the “in his bed” started to feel like part of the undercurrent of mild hysteria I thought I was hearing at many points in the story, as if all these events were being related by someone who’s really, really savoring the melodrama. (This is why I wound up calling Gregor – whose point of view dominates the story – a drama queen in one interview I gave about the translation.) So then I decided to stop trying to hide the phrase “in his bed” and instead make it bigger and louder and stick it right in the reader’s face: “right there in his bed.” All of a sudden the observation started making sense to me.

Will you hold it against me if I admit that the parts I most enjoyed translating were the really cruel and violent bits? (My warmup for this project was translating Jeremias Gotthelf’s 19th century horror novel The Black Spider, which also, by the way, uses the word Ungeziefer.) The thing is, for all the horror of Gregor’s situation, I am completely convinced that Kafka secretly found these parts uproariously hilarious and was chuckling aloud as he gorily laid out the hideous downward spiral of bug-boy’s degradation. The two climactic scenes that end the first two sections (one is excerpted here) both involve physical battles with Gregor’s father. This is in itself funny – after all, Gregor is now a big scary creature, and nonetheless here he is cowering and allowing himself to be abused and beaten down by domineering Dad. It’s like a revenge fantasy gone awry. Despite the fear Gregor strikes into the hearts of all his family members, he himself is paralyzed with concern for everyone else’s well-being (prompting several gorgeously neurotic inner monologues), and therefore he’s the one who gets stomped. The whole thing is completely unfair. Are you laughing yet?

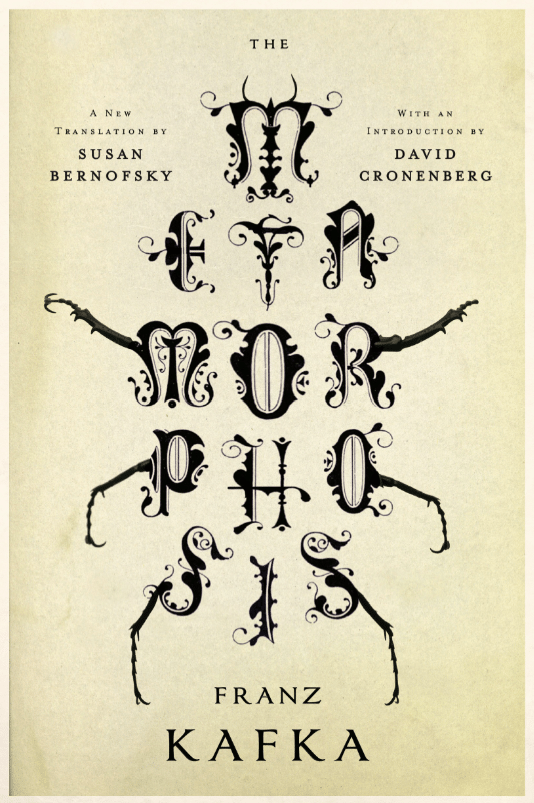

Originally my translation was commissioned as part of a new Norton Critical Edition of The Metamorphosis designed for classroom use, but since it takes a while to put together the accompanying articles for an edition of this sort (Kafka scholar Mark Anderson’s doing that), and the translation was meanwhile finished, Norton decided to publish the novella as a stand-alone volume first; the NCE will follow later this year. From my point of view the best thing about the decision to publish a trade edition was that it gave Norton the opportunity to commission an introduction for the book, and they picked legendary filmmaker David Cronenberg, whose human-all-too-human horror classic The Fly was in part informed by Kafka’s story. Cronenberg has some brilliant ideas about Kafka too, but I don’t want to give them away here. Another gorgeous thing about the edition is the cover created by London-based designer Jamie Keenan, who turned the letters of the word “metamorphosis” into the outlines of our beleaguered bug; I think it’s stunning.

Originally my translation was commissioned as part of a new Norton Critical Edition of The Metamorphosis designed for classroom use, but since it takes a while to put together the accompanying articles for an edition of this sort (Kafka scholar Mark Anderson’s doing that), and the translation was meanwhile finished, Norton decided to publish the novella as a stand-alone volume first; the NCE will follow later this year. From my point of view the best thing about the decision to publish a trade edition was that it gave Norton the opportunity to commission an introduction for the book, and they picked legendary filmmaker David Cronenberg, whose human-all-too-human horror classic The Fly was in part informed by Kafka’s story. Cronenberg has some brilliant ideas about Kafka too, but I don’t want to give them away here. Another gorgeous thing about the edition is the cover created by London-based designer Jamie Keenan, who turned the letters of the word “metamorphosis” into the outlines of our beleaguered bug; I think it’s stunning.

The Metamorphosis will officially be published on Monday, Jan. 20, but I’ve been hearing reports of early sightings on bookstore shelves, so I suppose that means the book is out! If you pick up a copy, I hope you’ll have at least half as much fun reading it as I had working on it. And if you’re around in NYC on Jan. 31 at 6:30 p.m., please come to the book’s launch party at NYU’s Deutsches Haus (42 Washington Mews), where I’ll be speaking with Jay Cantor, who’s just published a book of stories inspired by people in Kafka’s life, with Peter Mendelsund, designer of all those beautiful Kafka covers for Schocken, and Kafka-loving author and moderator Glenn Kurtz.

What a great opportunity! This is amazing–congratulations. ^_^